- What Are the Success Rates of CRISPR Gene Editing?

- Breaking Down CRISPR Success Rates: What Do the Numbers Mean?

- Key Factors Influencing CRISPR Gene Editing Effectiveness

- Clinical Trial Highlights: CRISPR’s Success in Genetic Disorders

- Comparing CRISPR Techniques: Base vs. Prime Editing Success

- Overcoming Hurdles: The Challenges Affecting CRISPR Success Rates

- Frequently Asked Questions

CRISPR gene editing success rates for genetic disorders vary widely, depending on the specific disease, delivery method, and editing technique used. Clinical trials have shown remarkable outcomes, with some achieving up to 90% correction of mutant proteins for conditions like transthyretin amyloidosis. Success is often measured by mutation correction efficiency, functional improvements, and the reduction of disease symptoms.

Breaking Down CRISPR Success Rates: What Do the Numbers Mean?

When discussing CRISPR success rates, it’s easy to get lost in the numbers. You might see figures ranging from 5% to over 90%, but these percentages refer to different stages and types of success. The most common mistake is assuming a single number tells the whole story. The reality is that “success” is measured at multiple levels: molecular efficiency, cellular outcome, and patient-level therapeutic benefit.

At the most basic level is editing efficiency. This refers to the percentage of target cells that have been successfully edited. For example, a study on using CRISPR for genetic disorders in embryos, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), reported a 72.4% success rate in producing embryos free of a specific mutation. This is a measure of pure technical success at the DNA level. However, this doesn’t automatically translate to a 72.4% cure rate in humans. The problem is that not all successful edits lead to the desired therapeutic outcome, and some can have unintended effects.

A more meaningful metric is the functional correction rate. This measures the restoration of normal gene function. For instance, in sickle cell disease trials, success is defined by the sustained production of functional hemoglobin, leading to the elimination of painful vaso-occlusive crises. Some trials have shown near-complete correction, restoring protein function to healthy levels. This is the metric that truly matters for patients, as it directly impacts their quality of life. Misunderstanding this difference leads many to misinterpret the technology’s current capabilities, thinking a high editing efficiency guarantees a cure, while ignoring the complexities of biological response and long-term stability.

Key Factors Influencing CRISPR Gene Editing Effectiveness

The effectiveness of any CRISPR therapy is not a lottery; it’s a result of several critical, interconnected factors. Ignoring these variables is a common misstep when evaluating the potential of a treatment. The primary determinant of success is the delivery mechanism. Getting the CRISPR-Cas9 system into the right cells without triggering a massive immune response is a major hurdle. Viral vectors (like AAVs) are efficient but can cause immune issues. Newer methods using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), like those in the first personalized CRISPR therapy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, offer a safer delivery route to organs like the liver, improving the overall success profile.

The second factor is the type of DNA repair pathway the cell uses. CRISPR makes the cut, but the cell does the repair. There are two main paths: a quick-and-dirty method called NHEJ and a precise one called Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). For many genetic disorders, HDR is required for a true “correction,” but cells often default to the less precise NHEJ. The efficiency of HDR can be low, which directly impacts the therapeutic success rate. Much of the ongoing research focuses on pushing cells to favor the HDR pathway to ensure the genetic fix is accurate and permanent.

Finally, the target cell type itself plays a huge role. Editing hematopoietic stem cells (HSPCs) to treat blood disorders like sickle cell anemia presents different challenges than editing liver cells or lung cells. Some cells are simply harder to reach and edit. The number of cells that need to be corrected to alleviate the disease also varies. For some conditions, correcting just 10-20% of the cells might be enough for a therapeutic effect, while others may require a much higher threshold. This variability is why you see such a wide range of success rates across different clinical trials.

Clinical Trial Highlights: CRISPR’s Success in Genetic Disorders

Abstract discussions about success rates are useful, but the real proof is in clinical trial results. Over the last few years, CRISPR has moved from the lab to treating patients with devastating genetic disorders, and the outcomes are highly encouraging. The most prominent success stories involve sickle cell disease (SCD) and beta-thalassemia. In multiple trials, patients treated with CRISPR-edited stem cells have become transfusion-independent and free of the debilitating pain crises that define SCD. These results represent a functional cure and showcase what’s possible when the technology works as intended.

Another area of significant progress is transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis, a disease where a misfolded protein builds up in organs. A groundbreaking trial used an LNP-based infusion to deliver CRISPR directly into the liver. The results were stunning, showing up to a 90% reduction in the disease-causing protein. This demonstrated not only high efficiency but also the viability of in vivo (in the body) editing, a major step forward from the ex vivo (outside the body) methods used for blood disorders.

Beyond these, trials are underway for numerous other conditions, including cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and even certain types of cancer. For example, personalized therapies are emerging for rare genetic diseases, such as the one reported by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for a child with a rare metabolic disorder. While these are early days, the consistent positive data across different diseases and delivery methods signal that CRISPR is on the path to becoming a mainstream therapeutic tool.

Comparing CRISPR Techniques: Base vs. Prime Editing Success

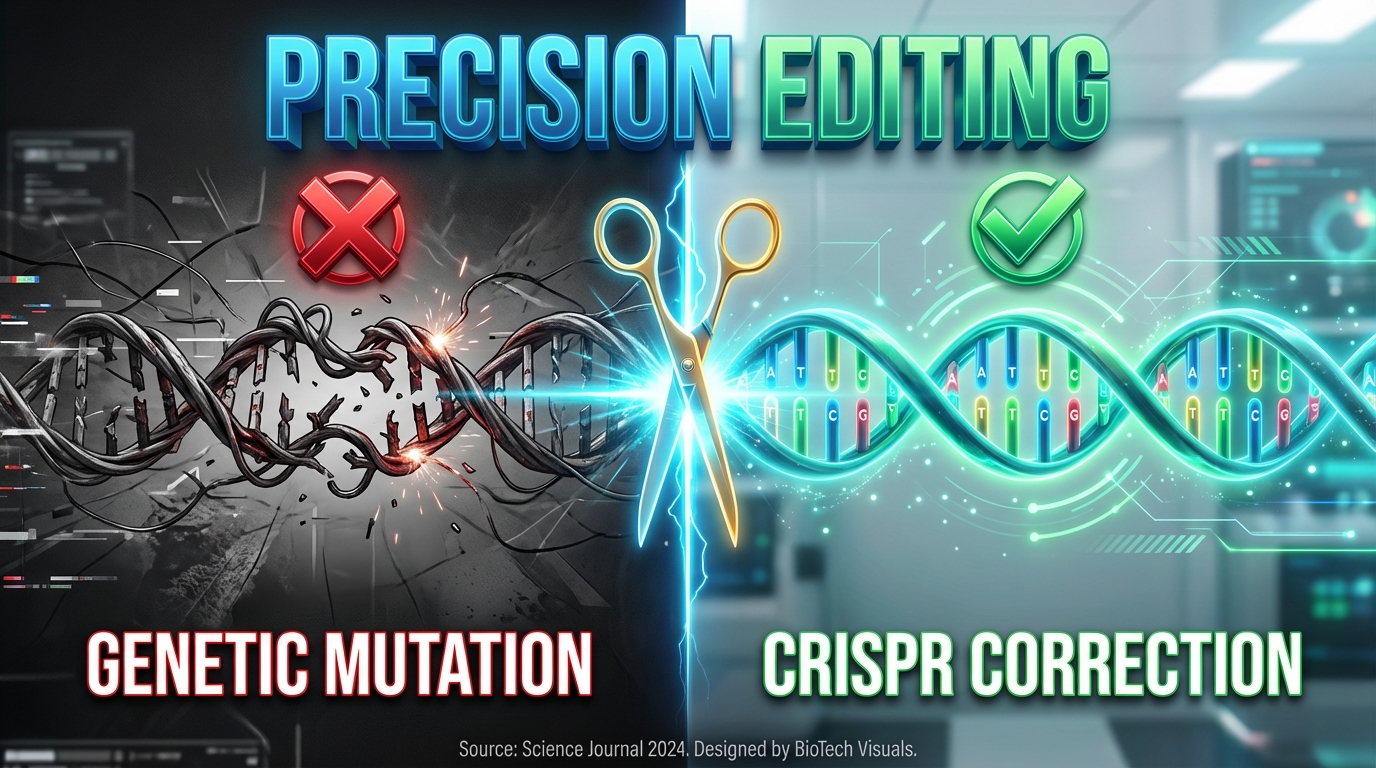

The original CRISPR-Cas9 system is like a pair of molecular scissors—it cuts DNA. While powerful, this can lead to unintended edits and relies on the cell’s unreliable HDR pathway for precise fixes. This limitation sparked the development of newer, more precise technologies like base editing and prime editing. Many people mistakenly lump all “CRISPR” together, but these newer methods offer distinct advantages in both safety and success rates.

Base editing acts more like a pencil with an eraser. It chemically converts one DNA letter to another without making a double-strand break in the DNA. This significantly reduces the risk of off-target mutations and large DNA deletions. For genetic disorders caused by a single-letter mutation (point mutations), base editing is a far more efficient and safer tool. This has been demonstrated in models for diseases like cystic fibrosis, where base editors successfully repaired the causative mutations in vitro.

Prime editing is even more sophisticated, often described as a genetic “search and replace” tool. It can correct small insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible single-letter conversions. Like base editing, it avoids the double-strand breaks of traditional CRISPR-Cas9, offering a superior safety profile. A scientific review in the journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy highlights how such improvements increase precision. Early data suggests prime editing could be highly effective for a wider range of genetic diseases that base editing can’t address.

| Technique | Mechanism | Primary Use Case | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Cuts both DNA strands | Gene disruption or insertion/deletion | Higher risk of off-target effects and large deletions |

| Base Editing | Chemically converts a single DNA base | Correcting single-letter point mutations | Lower risk; avoids double-strand breaks |

| Prime Editing | Search and replace gene sequences | Correcting point mutations, insertions, deletions | Highest precision; avoids double-strand breaks |

Overcoming Hurdles: The Challenges Affecting CRISPR Success Rates

Despite the incredible successes, CRISPR gene editing is not yet a perfect science. Several significant challenges must be addressed to ensure consistent and safe outcomes. The most discussed issue is off-target effects—the risk that the CRISPR system edits the wrong part of the genome. While newer techniques have drastically reduced this risk, it remains a primary safety concern that regulators watch closely. An even more subtle risk is on-target, but unintended, edits like large deletions or retrotransposition events, which one study reported occurring at a 5-6% rate. These could have long-term consequences, including the theoretical risk of initiating tumors.

The second major challenge remains delivery and immunogenicity. As mentioned, getting the editing machinery to the right place is half the battle. The other half is preventing the patient’s immune system from attacking the CRISPR components (which are often derived from bacteria) or the delivery vehicle. An immune response can not only neutralize the therapy before it works but also cause harmful inflammation. Overcoming this requires engineering less immunogenic systems and refining delivery protocols.

Finally, there are challenges of scale and cost. Personalized cell therapies, where a patient’s own cells are removed, edited, and reinfused, are incredibly complex and expensive, running into millions of dollars per patient. For CRISPR to become a mainstream cure for common genetic disorders, more scalable and cost-effective “off-the-shelf” solutions are needed. These biological and logistical hurdles are the focus of intense research and development, and solving them will be key to unlocking CRISPR’s full potential for all patients.

Frequently Asked Questions

How effective is CRISPR in treating rare genetic disorders?

CRISPR is showing exceptional promise for rare genetic disorders, particularly those caused by a single gene mutation. The world’s first personalized CRISPR therapy was used to treat a child with CPS1 deficiency, a rare metabolic disorder, with remarkable improvements. The effectiveness depends on whether the genetic error can be precisely corrected with tools like base or prime editing and whether the target cells (e.g., in the liver or bone marrow) can be reached safely. For many rare diseases, CRISPR offers the first real hope for a cure rather than just symptom management.

What are the main challenges in using CRISPR for clinical applications?

The three main challenges are 1) Delivery: Safely and efficiently getting the CRISPR machinery into the target cells without causing an immune reaction. 2) Specificity: Ensuring the edits happen only at the intended location in the genome (on-target) and not anywhere else (off-target). 3) Long-term Safety: Understanding and mitigating any long-term risks associated with altering a person’s DNA, including the potential for unintended mutations or cellular changes over time. Overcoming these hurdles is the key to widespread clinical adoption.

How does prime editing compare to traditional CRISPR in terms of safety and efficacy?

Prime editing offers significant advantages in both safety and efficacy. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9, which makes a double-strand cut in the DNA, prime editing uses a “nick and replace” mechanism that only cuts one strand. This dramatically reduces the risk of off-target errors and large, unintended DNA deletions. In terms of efficacy, prime editing is more versatile, capable of correcting a wider variety of mutations than base editing. It is considered a safer and more precise tool for correcting the genetic defects underlying many diseases.