- Quick Summary: Life in the Hadal Zone

- 1. The Hadal Zone: Geography of the Mariana Trench

- 2. Chemosynthesis: How Life Survives Without Sunlight

- 3. Piezolytes: The Biochemistry of Pressure Resistance

- 4. Recent Discoveries: From Snailfish to Flatworms

- 5. Bioluminescence: The Language of the Dark

- 6. The Future: Deep-Sea Technology and Conservation

- Frequently Asked Questions

What lives in the deepest ocean trenches and how do they survive?

Life in the deepest ocean trenches (the Hadal Zone, 6,000–11,000 meters) is sustained by chemosynthesis and extreme biological adaptations. Unlike surface life, organisms like Mariana snailfish and giant tubeworms rely on chemical energy (hydrogen sulfide/methane) rather than sunlight. They survive crushing pressures (up to 1,000 atmospheres) using specialized molecules called piezolytes (like TMAO) that prevent their proteins from warping, allowing complex marine biology to thrive in unexplored depths.

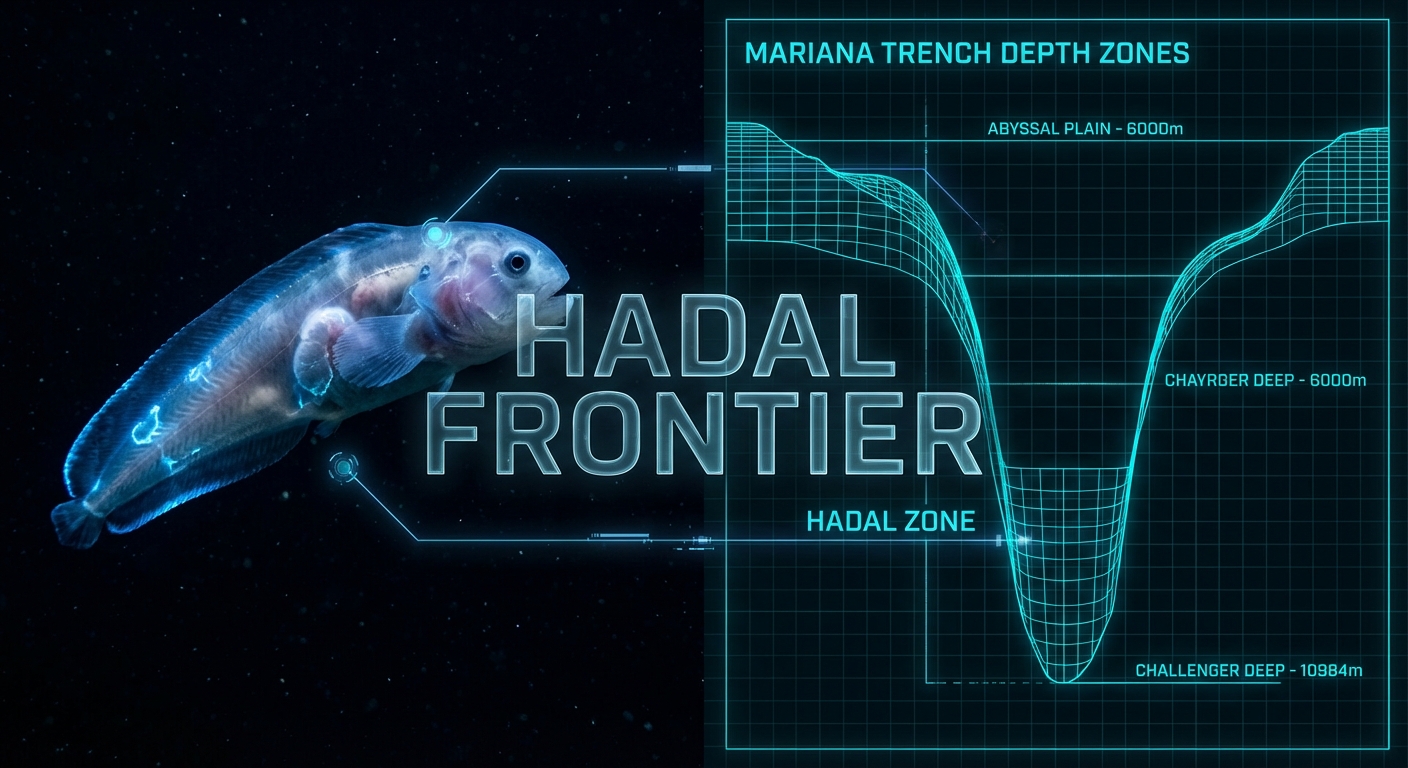

1. The Hadal Zone: Geography of the Mariana Trench

The ocean is divided into layers, but the Hadal Zone is the final frontier. Beginning at 6,000 meters (19,685 feet) and extending to the bottom of the deepest trenches, this zone is named after Hades, the Greek underworld. It accounts for the deepest 45% of the ocean’s depth range but represents less than 2% of the seafloor’s total area.

The Challenger Deep:

The deepest known point on Earth is the Challenger Deep within the Mariana Trench, plunging approximately 10,935 meters (35,876 feet). To put this in perspective, if you dropped Mount Everest into the trench, its peak would still be over 2 kilometers underwater. Conditions here are extreme: temperatures hover just above freezing (1–4°C), and the pressure exceeds 8 tons per square inch—roughly equivalent to an elephant standing on your thumb.

Why It Matters:

For decades, scientists believed this zone was lifeless. Recent expeditions have proven otherwise. The geography itself—steep V-shaped canyons—traps organic matter falling from above (marine snow), creating nutrient-dense "depocenters" that support surprisingly high biomass.

2. Chemosynthesis: How Life Survives Without Sunlight

In the absence of sunlight, photosynthesis is impossible. Instead, the foundation of the food web in deep trenches is chemosynthesis. This process occurs primarily around hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, where bacteria convert toxic chemicals into usable energy.

The Mechanism:

Chemosynthetic bacteria oxidize inorganic molecules like hydrogen sulfide (H2S) or methane released from the Earth’s crust. This oxidation releases energy, which the bacteria use to fix carbon dioxide into sugar. This is the exact chemical opposite of how we typically understand life on Earth. As detailed in our guide to Hydrothermal Vents and Alien Biology, these bacteria often form symbiotic relationships with larger animals, living inside their tissues to provide food directly.

Key Organism: Giant Tubeworms

Recent discoveries have found these communities at record depths. A 2025 report noted the discovery of tubeworm colonies at 9,533 meters, pushing the known boundaries of where chemosynthesis can sustain complex animal life.

3. Piezolytes: The Biochemistry of Pressure Resistance

The most common question regarding deep-sea biology is: Why don’t the fish get crushed? The answer lies in biochemistry, specifically the use of piezolytes.

The Problem:

High pressure forces water molecules into the interior of proteins, causing them to distort and lose their function. For a standard surface fish, a trip to the Mariana Trench would cause its enzymes to stop working, leading to immediate metabolic failure.

The Solution (TMAO):

Hadal organisms accumulate high concentrations of Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in their cells. TMAO is a "chemical chaperone"—it binds to water molecules and structures them in a way that prevents them from crushing proteins. There is a direct linear relationship between depth and TMAO concentration: the deeper a fish lives, the fishier it smells (as TMAO is what gives decomposing seafood its odor).

Recommended Reading:

For those interested in the physiological details of these adaptations, Deep-Sea Biology offers an academic-level analysis of organismal adaptation.

4. Recent Discoveries: From Snailfish to Flatworms

Exploration technology has improved rapidly, allowing for the discovery of species that challenge our classification systems. Identifying these creatures often requires advanced methods, as outlined in our Marine Biology Species Identification Guide.

The Mariana Snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei):

Currently holding the record for the deepest collected fish (approx. 8,000m), the snailfish is a marvel of evolution. It has no scales, a translucent skin, and a skeleton made largely of cartilage rather than bone to withstand pressure. Unlike the monstrous visages of anglerfish, snailfish are small, tadpole-like, and surprisingly cute.

Black Eggs of the Abyss:

A recent and surprising discovery involves the finding of jet-black flatworm eggs at 6,200 meters. This finding, highlighted by Popular Mechanics, suggests that even simple organisms like platyhelminths have conquered the abyss, utilizing reproductive strategies we have yet to fully understand.

Recommended Visual Resource:

To see these creatures in high-definition, The Deep provides some of the best photographic evidence available of these new species.

5. Bioluminescence: The Language of the Dark

While the very bottom of the trench (the hadal zone) is often sparsely populated, the waters directly above it are teeming with light. Bioluminescence is used for everything from predation to mating.

The Mechanism:

As we explored in our article on Marine Bioluminescence, animals use a reaction between luciferin and oxygen to create cold light. In the deep trenches, this often takes the form of "burglar alarms"—flashes of light intended to startle a predator or attract an even bigger predator to eat the attacker.

6. The Future: Deep-Sea Technology and Conservation

According to the UN Ocean Decade, nearly three-quarters of the seafloor remains unmapped. However, the race to map it is driven by two opposing forces: scientific curiosity and industrial greed.

The Mining Threat:

The same vents that host unique life also create massive deposits of rare earth metals. Deep-sea mining proposes to harvest these nodules, which would likely destroy these fragile ecosystems before we have even documented them. The sediment plumes alone could choke filter feeders miles away from the mining site.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the deepest fish ever recorded?

The deepest fish ever filmed is a species of snailfish (genus Pseudoliparis) found in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench at a depth of 8,336 meters (27,349 feet). It is hypothesized that 8,400 meters is the biological limit for fish due to the physiological constraints of osmosis and protein stability.

Do megalodons live in the Mariana Trench?

No. This is a popular myth. The megalodon was a warm-water shark that would not survive the freezing temperatures of the deep ocean. furthermore, there is not enough biomass (food) in the hadal zone to support a predator of that size.

How do scientists explore the deepest trenches?

Exploration is conducted using Human Occupied Vehicles (HOVs) like the Limiting Factor and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). These vessels utilize titanium pressure hulls and syntactic foam for buoyancy to withstand the immense pressure.

What do animals in the trench eat?

They rely on two food sources: Marine Snow (organic detritus falling from the surface) and Chemosynthesis (local production of food by bacteria). Scavengers like amphipods swarm carrion falls, while tubeworms rely on their symbiotic bacteria.

Why is the ocean floor not flat?

The seafloor is shaped by plate tectonics. Trenches like the Mariana are formed at subduction zones, where one tectonic plate is forced beneath another, creating a deep V-shaped depression in the Earth’s crust.