- Direct Answer: The Neuroscience of Memory Formation

- 1. The Standard Model: From Scratchpad to Hard Drive

- 2. The Molecular Machinery: Synaptic Plasticity & LTP

- 3. New Research: The ‘Simultaneous Storage’ Discovery

- 4. The Critical Role of Sleep and Replay

- 5. The Chemical Switches: CaMKII and Protein Synthesis

- Recommended Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

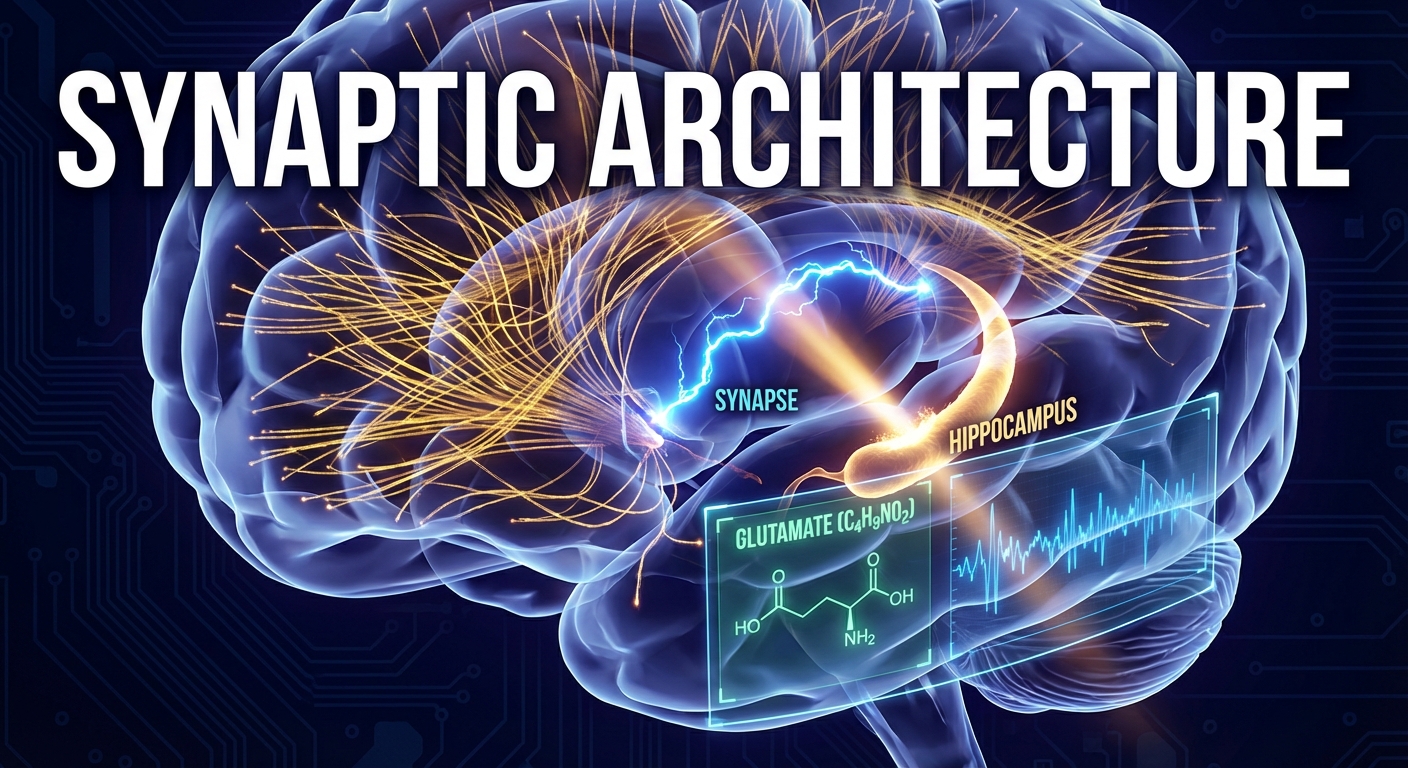

Long-term memory formation is a biological process driven by Long-Term Potentiation (LTP). It begins with encoding in the hippocampus, where specific patterns of neurons fire together. Through a process called synaptic consolidation, repeated firing triggers chemical changes (protein synthesis) that strengthen the connections (synapses) between these neurons. Over time, via systems consolidation, these memories are transferred to the neocortex for permanent storage, transforming a fragile electrical signal into a stable physical structure.

1. The Standard Model: From Scratchpad to Hard Drive

To understand memory, you must first understand the architecture of the brain’s storage systems. For decades, neuroscientists have relied on the Standard Model of Systems Consolidation. In this framework, the brain has two distinct storage units: the Hippocampus and the Neocortex.

Think of the Hippocampus as your computer’s RAM (Random Access Memory). It is fast, highly plastic, and responsible for rapidly capturing new information—like the name of a person you just met. However, it is temporary. If you do not save the data, it is overwritten.

The Neocortex acts as the Hard Drive. It is slower to learn but extremely stable. The process of learning is essentially the transfer of data from the temporary Hippocampus to the permanent Neocortex. This dialogue usually happens when you are offline—during sleep. For a deeper look at how the brain manages this transfer during rest, read our guide on the role of sleep in memory consolidation.

Key Takeaway: You cannot form long-term memories without the Hippocampus initially, but eventually, the memory becomes independent of it. This is why patients with hippocampal damage (like the famous patient H.M.) can remember their childhood (stored in the cortex) but cannot form new memories.

2. The Molecular Machinery: Synaptic Plasticity & LTP

The physical mechanism behind memory is Synaptic Plasticity—the ability of synapses (the gaps between neurons) to change their strength. The gold standard for this process is Long-Term Potentiation (LTP).

What is LTP?

Imagine a grassy field. If you walk across it once, the grass springs back (short-term memory). If you walk the same path repeatedly, a dirt trail forms. If you pave it, it becomes a permanent road (long-term memory). LTP is the paving process.

Biologically, this involves two key receptors: AMPA and NMDA. When a neuron is stimulated strongly enough, magnesium blocks are removed from NMDA receptors, allowing Calcium to flood the cell. This calcium surge triggers a chain reaction that inserts more AMPA receptors into the synapse. The result? The next time that neuron receives a signal, it responds faster and stronger. This strengthening is the cellular basis of learning.

3. New Research: The ‘Simultaneous Storage’ Discovery

While the Standard Model is still taught, recent findings have challenged its simplicity. A landmark study published by MIT neuroscientists suggests that the brain might not just “transfer” memories, but create two copies simultaneously.

The Silent Memory:

The research revealed that when a memory is formed, it is encoded in the Hippocampus (for immediate use) and simultaneously in the Neocortex. However, the copy in the Neocortex is “silent” or immature—it exists but cannot be retrieved yet. Over weeks, the hippocampal memory fades while the cortical memory matures and becomes active.

This fundamentally changes how we view memory loss. It suggests that long-term memories are not just moved; they are cultivated. This aligns with current neuroscience research on memory formation, which emphasizes that “forgetting” might sometimes be a retrieval failure of these silent engrams rather than a deletion of data.

4. The Critical Role of Sleep and Replay

You cannot hack memory formation by skipping sleep. The consolidation process—making the memory permanent—is metabolically expensive and requires the brain to be offline.

During Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS), the brain engages in Hippocampal Replay. The neurons that fired during the day fire again at high speed (in a compressed timeline), effectively “teaching” the neocortex the new information. This is why “cramming” for an exam rarely works for long-term retention; without the sleep cycle to replay and cement the synaptic changes, the metabolic trail washes away.

The Mechanism:

According to the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, this consolidation phase is where the memory becomes resistant to interference. If you interrupt this process (through sleep deprivation or stress), the protein synthesis required to “lock” the synapse fails.

5. The Chemical Switches: CaMKII and Protein Synthesis

Ultimately, a long-term memory is a physical structure made of proteins. The switch that turns short-term electrical signals into long-term physical structures is a molecule called CaMKII (Calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II).

Research from the Max Planck Florida Institute has shown that CaMKII acts as a molecular memory switch. When Calcium enters the cell (during LTP), CaMKII is activated and stays active even after the calcium is gone. This persistent activity drives Gene Expression.

From DNA to Memory:

This signal travels to the nucleus of the neuron, activating genes (like CREB) that order the production of new proteins. These proteins build new synaptic terminals, literally growing the brain’s hardware. This structural change is what neuroplasticity rewires the aging brain with—it is the physical manifestation of experience.

Recommended Resources

To truly understand the depth of these mechanisms, we recommend looking at the foundational texts that bridge the gap between cognitive psychology and molecular biology.

For a more accessible but scientifically rigorous look at why memory fails and how it succeeds, “The Seven Sins of Memory” is an essential read.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between LTP and LTD?

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) strengthens synapses, making it easier for neurons to communicate (learning). Long-Term Depression (LTD) weakens synapses (forgetting). Both are essential; without LTD, your brain would become saturated with noise, making it impossible to prioritize important information.

Does memory formation change with age?

Yes. While the mechanism (LTP) remains the same, the chemical environment changes. Aging often leads to a decrease in BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) and increased inflammation, which makes it harder to sustain the “late-phase” protein synthesis required for permanent storage.

Can long-term memories form instantly?

Generally, no. Most memories require consolidation time. However, highly emotional events (trauma) can bypass the slow consolidation process via the Amygdala, which releases stress hormones that immediately “tag” a memory as high-priority, leading to rapid, sometimes intrusive, encoding.

What role does DNA play in memory?

DNA is the blueprint. When a long-term memory is formed, genes must be “expressed” (turned on) to produce the proteins needed to build new synaptic connections. Drugs that block protein synthesis can theoretically erase the ability to form new long-term memories.

Is the hippocampus the only place for memory?

No. The hippocampus is the “librarian” that catalogs and retrieves episodic memories (events). Procedural memories (like riding a bike) are stored in the Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum, while emotional memories rely heavily on the Amygdala.