- Quick Summary: Hydrothermal Vents Defined

- 1. The 1977 Discovery: How Alvin Changed Biology

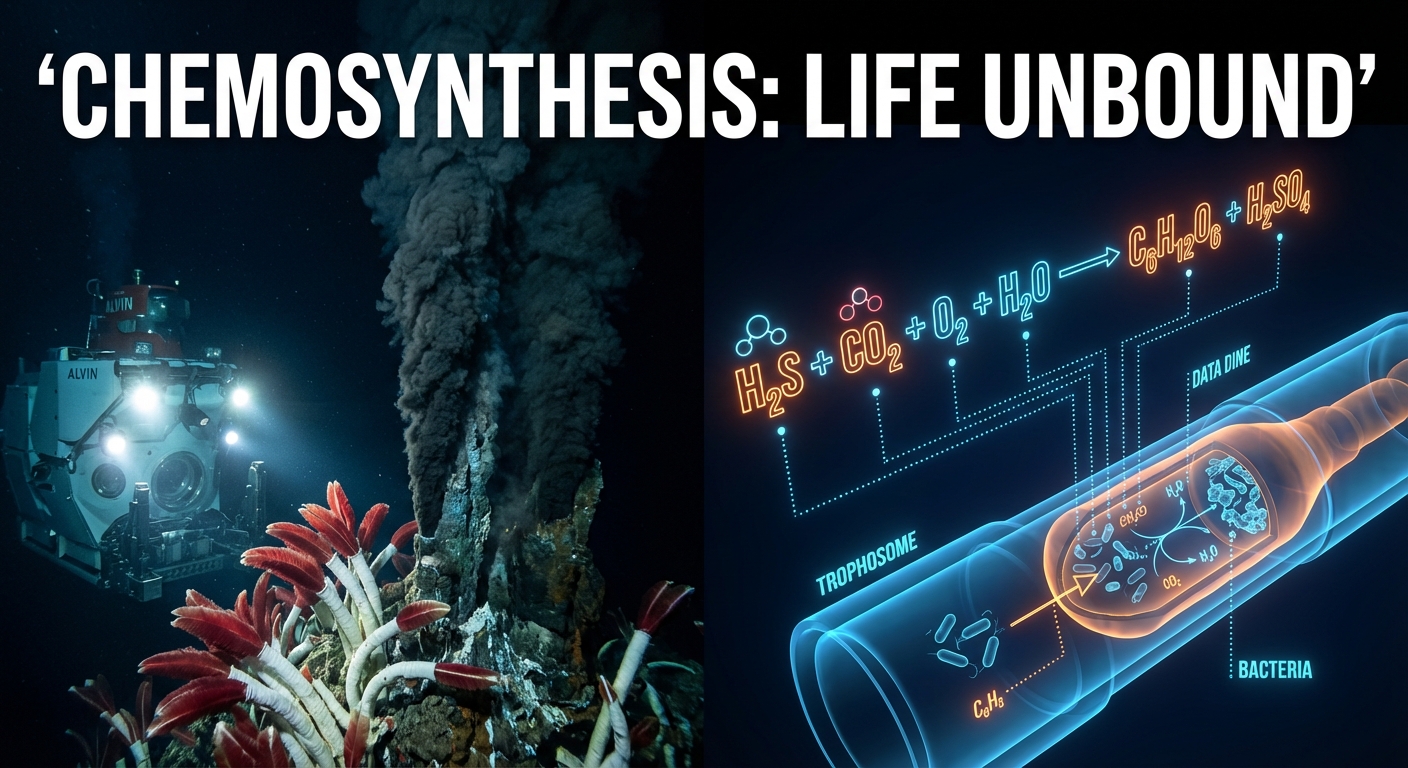

- 2. Chemosynthesis: The Mechanics of H2S Oxidation

- 3. The Trophosome: Anatomy of a Symbiotic Miracle

- 4. From Earth to Europa: The Astrobiology Link

- 5. The Future: Deep-Sea Mining and Conservation

- Frequently Asked Questions

What are hydrothermal vents and how do they support life?

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seafloor where geothermally heated water releases mineral-rich fluids. Unlike surface ecosystems that rely on photosynthesis, vent communities are powered by chemosynthesis. In this process, chemosynthetic bacteria oxidize toxic chemicals like hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and methane to generate energy (ATP), which they use to convert carbon dioxide into sugar. This microbial foundation supports massive organisms like Riftia pachyptila (giant tubeworms) through obligate symbiosis.

1. The 1977 Discovery: How Alvin Changed Biology

Before 1977, the central dogma of biology was simple: all life ultimately depends on the sun. Photosynthesis was the only known foundation for a food web. This paradigm was shattered during an expedition by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) to the Galápagos Rift.

The Event:

Geologists aboard the submersible Alvin were searching for heat signatures to prove the theory of plate tectonics. Instead, they found biology. At 2,500 meters deep, where pressure crushes standard equipment and darkness is absolute, they discovered thriving communities of giant clams, mussels, and 6-foot-tall tubeworms.

The Significance:

This was not just a new species discovery; it was the discovery of a completely new metabolic pathway for life. As detailed in our article on Marine Bioluminescence and Deep Sea Creatures, the deep ocean was previously thought to be a desert. The existence of these "oases of life" proved that life could thrive in toxic, high-pressure, and high-temperature environments provided there is a chemical energy source.

Recommended Reading:

For a firsthand account of the history of deep-sea exploration, The Eternal Darkness by Robert Ballard (the man who found the Titanic) offers an incredible narrative of how these discoveries unfolded.

2. Chemosynthesis: The Mechanics of H2S Oxidation

To understand hydrothermal vents, you must understand the chemistry that fuels them. While plants use photons (light energy) to strip electrons from water, vent bacteria use chemical energy to strip electrons from hydrogen sulfide.

The Chemical Equation:

The simplified reaction for sulfide oxidation is:

CO2 + O2 + 4H2S → CH2O (Sugar) + 4S + 3H2O

The Mechanism:

Vent fluids exit the crust at temperatures up to 400°C (750°F), loaded with dissolved minerals. When this superheated acidic fluid hits the near-freezing seawater, the minerals precipitate, forming the iconic "chimneys" or black smokers. The bacteria, known as chemoautotrophs, harvest the sulfide ions. They oxidize the sulfide (removing electrons) and use the released energy to power the Calvin Cycle, fixing inorganic carbon into organic sugar.

Common Misconception:

People often assume these bacteria only exist on the rocks. In reality, they are also free-floating in the plume and, most importantly, living inside the tissues of larger animals. Identifying these microscopic interactions often requires advanced techniques, as discussed in our Marine Biology Species Identification Guide.

3. The Trophosome: Anatomy of a Symbiotic Miracle

The most defining organism of the hydrothermal vent is the Giant Tubeworm, Riftia pachyptila. These worms have no mouth, no gut, and no anus. Yet, they grow faster than almost any other marine invertebrate.

How Do They Eat?

The secret lies in a specialized organ called the trophosome. This organ takes up most of the worm’s body cavity and is packed with billions of symbiotic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria.

The Hemoglobin Trick:

Riftia has bright red plumes because its blood is rich in a specialized hemoglobin. Unlike human hemoglobin, which transports only oxygen, tubeworm hemoglobin binds both oxygen and hydrogen sulfide simultaneously (and reversibly). It acts as a delivery truck, transporting the toxic sulfide safely to the bacteria in the trophosome without poisoning the worm itself. The bacteria consume the sulfide and release sugars, feeding the worm from the inside out.

Data Insight:

According to research from NOAA, this symbiosis is so efficient that tubeworms can grow up to 85 cm (33 inches) per year, a growth rate rivaling the fastest-growing plants on land.

4. From Earth to Europa: The Astrobiology Link

The study of hydrothermal vents has moved beyond marine biology and into the realm of astrobiology. If life can begin and thrive in the sunless, high-pressure depths of Earth’s oceans, could it exist elsewhere?

The Target Worlds:

NASA and other space agencies are looking at "Ocean Worlds" like Europa (a moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn). Both moons have ice crusts covering vast subsurface saltwater oceans. Cassini probe data from Enceladus has detected plumes of water vapor containing hydrogen and silica nanograins—strong evidence of active hydrothermal activity on the seafloor.

The Model:

Earth’s vent ecosystems serve as the primary biological model for these missions. We are no longer looking for little green men; we are looking for chemosynthetic signatures. This shift in focus is why deep-sea biology is currently one of the most well-funded areas of space research.

Recommended Reading:

For a broader look at how extreme life forms survive in the ocean’s harshest environments, The Extreme Life of the Sea provides excellent context on the adaptations required for deep-sea survival.

5. The Future: Deep-Sea Mining and Conservation

Hydrothermal vents are not just biological wonders; they are geological treasure chests. As the superheated water cools, it deposits massive amounts of minerals, forming Seafloor Massive Sulfides (SMS). These deposits are rich in copper, gold, zinc, and rare earth elements.

The Conflict:

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is currently drafting regulations for deep-sea mining. The technology exists to strip-mine these vents, but doing so would likely obliterate the ecosystems relying on them. Unlike a forest which can regrow relatively quickly, vent communities are often endemic to specific sites. Destroying a vent field could mean the extinction of species we haven’t even named yet.

Why It Matters:

These organisms are potential goldmines for biotechnology. Enzymes isolated from vent bacteria (extremophiles) are already used in DNA sequencing and industrial processing because they can withstand high heat. Preserving this biodiversity is not just an ethical choice; it is an economic imperative for future medical discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

How hot is the water coming out of a hydrothermal vent?

The fluid can reach temperatures of up to 400°C (750°F). It does not boil because the extreme pressure of the deep ocean (over 250 atmospheres) keeps the water in a liquid state. However, the surrounding seawater is near freezing (~2°C), creating a massive temperature gradient.

Do hydrothermal vents last forever?

No. Hydrothermal vents are temporary features. They can remain active for decades or even a century, but eventually, the geological plumbing clogs or the tectonic plates shift, cutting off the heat source. When a vent goes dormant, the chemosynthetic community dies out.

Are black smokers the only type of vent?

No. There are also white smokers, which release cooler water rich in barium, calcium, and silicon. Additionally, the Lost City Hydrothermal Field features vents driven by a chemical reaction called serpentinization, rather than volcanic heat, producing highly alkaline fluids.

Can humans visit these vents?

Humans visit these vents regularly using Deep Submergence Vehicles (DSVs) like Alvin (USA), Shinkai 6500 (Japan), and Nautile (France). However, most modern research is done using Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) connected to the ship by a tether.

What is the difference between chemosynthesis and photosynthesis?

The main difference is the energy source. Photosynthesis uses solar energy (sunlight) to convert CO2 into sugar. Chemosynthesis uses chemical energy (derived from the oxidation of inorganic molecules like hydrogen sulfide or methane) to convert CO2 into sugar.